Mandarin's four tones intimidate new learners—the same syllable "ma" can mean mother, hemp, horse, or scold depending on pitch. But tones follow predictable patterns, and with the right approach, they become second nature.

Understanding the Four Tones

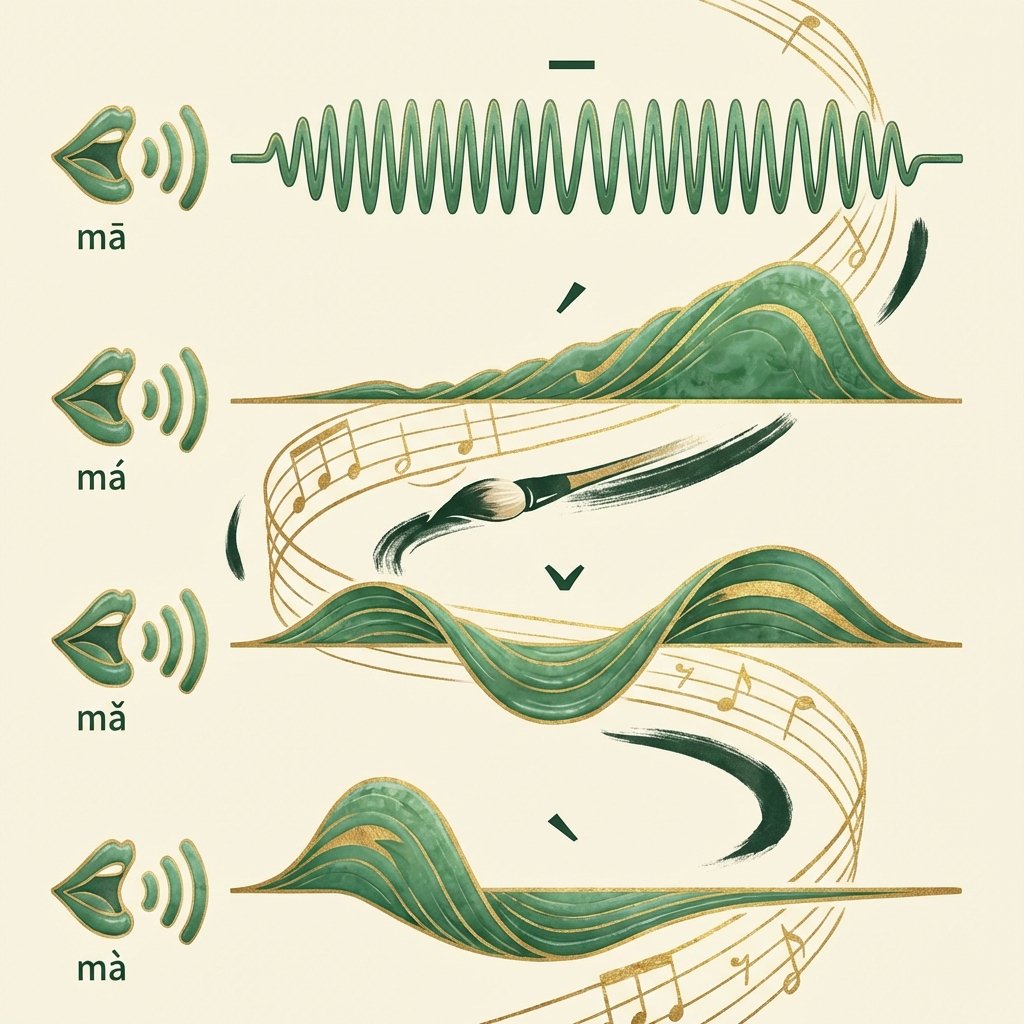

First tone (ˉ) stays high and flat, like sustaining a musical note.

Second

tone (ˊ) rises from middle to high, like asking "What?" in surprise.

Third tone

(ˇ) dips low then rises, like saying "Well..." thoughtfully.

Fourth tone

(ˋ) drops sharply from high to low, like giving a firm command.

Why Tones Matter

Tones aren't optional extras—they're essential meaning-carriers. Say 买 (mǎi, third tone) correctly and you're buying something. Slip into 卖 (mài, fourth tone) and you're selling instead. Native speakers depend on tones to understand speech, and wrong tones cause genuine confusion, not just accent differences.

Common Tone Mistakes

English speakers often flatten all tones, making everything sound like first tone. The third tone causes the most trouble—learners frequently don't go low enough or forget the slight rise at the end. Fourth tone sometimes becomes too abrupt. Second tone often isn't high enough at the finish.

Effective Practice Methods

Practice tones in pairs and groups, not isolation. Real speech contains tone combinations, and some combinations are tricky (two third tones in a row actually change—the first becomes second tone). Record yourself and compare to native speakers. Use hand gestures to physically trace tone shapes while speaking.

Building Tone Awareness

Listen actively to Chinese content, focusing specifically on tones rather than meaning. Shadow native speakers—pause audio and repeat immediately with exact intonation. Learn new vocabulary with tones from the start; it's much harder to correct ingrained wrong tones than to learn correctly initially.

Perfect Your Pronunciation

Avena's AI tutor identifies your specific tone weaknesses and provides targeted practice with native audio.

Try Avena Free